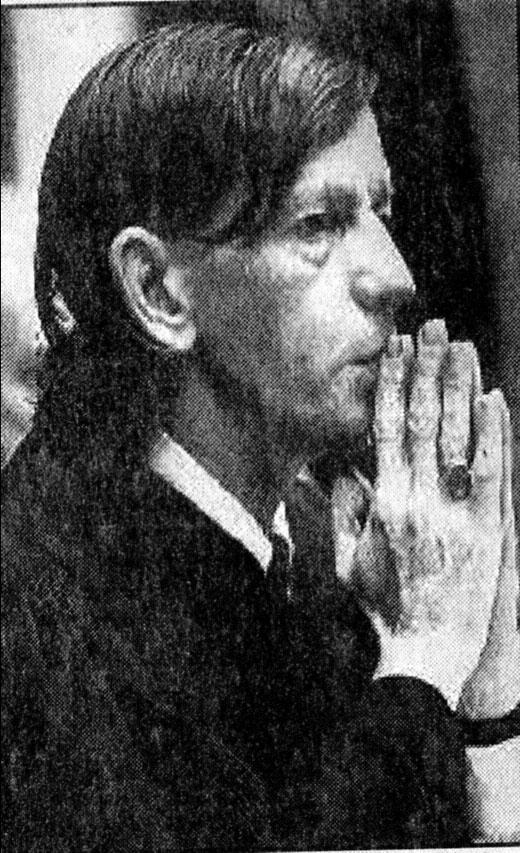

Judge Frank Mahady's Decision in the 1984 Island Pond Case

Jun 11, 2024

STATE OF VERMONT

ORLEANS COUNTY, ss.

IN RE: CERTAIN CHILDREN

DISTRICT COURT OF VERMONT

UNIT NO. 3, ORLEANS CIRCUIT

[Filed - June 26, 1984]

OPINION: DETENTION ORDER

At dawn on June 22, 1984, 112 children were taken into custody by the State in Island Pond, Vermont. They were delivered to this Court pursuant to 33 V.S.A. §640 (2) at which time the State requested a blanket order of detention under 33 V.S.A. §641.

The Court refused to proceed ex parte and appointed counsel for the parents as well as counsel for the children on its own motion pursuant to 33 V.S.A. §653. Individual, contested hearings were then held with regard to the State's request for Section 641 orders of detention.

Each such request was denied by the Court from the bench, and the Court indicated that this opinion regarding those Orders would subsequently be filed.

(A.)

One purpose of Vermont's Juvenile Procedures is "to provide for the care, protection and wholesome moral, mental and physical development of children." 33 V.S.A. §631 (a) (1).

However, it is the unequivocal goal of the Vermont legislature "to achieve [this] purpose, whenever possible, in a family environment, separating the child from his parents only when necessary for his welfare." 33 V.S.A. §631 (a) (3). (emphasis applied).

This clause recognizes the fact that "the freedom of children and parents to relate to one another in the context of the family, free of governmental interference, is a basic liberty long established in our constitutional law." In re N.H., 135 Vt. 230, 236 (1977) [Hill, J.]; see, Stanley v. Illinois, 405 U.S. 645 (1972); Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U.S. 158 (1944); Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923). The legislature, in Section 631 (a) (3), has expressly provided that a child be separated from his parents only when necessary precisely in order to ensure that this fundamental liberty will not be unduly tampered with. In re N.H., op. Cit.; In re J.M., 131 Vt. 604, 609 (1972).

(B.)

When the Court applies these clear and unambiguous constitutional and legislative mandates, regard must be had for compelling parental rights. In re N.H., op. Cit. At 237. Therefore, Vermont's Courts "have proceeded with great caution, and continue to do so in light of the awesome power involved" with the removal of children from their parents. In re G.V. and R.P., 136 Vt. 499, 503 (1978); In re D.R., 136 Vt. 478 (1978); In re J. & J.W., 134 Vt. 480 (1976).

Of course, the best interests of the child involved is the principal concern in juvenile proceedings. However, as Mr. Justice Larrow has pointed out, "the 'best interest of the child' is a useful maximum, but it comes into play only when there is a legal jurisdiction." In re J. & J.W., op. Cit. At 485, 486 (Larrow, J., concurring).

(C.)

It is in this context that Mr. Justice Hill, writing for a unanimous Court, explicitly set out the controlling rule of law: "Accordingly, any time the State seeks to interfere with the rights of parents on the generalized assumption that the children are in need of care and supervision, it must first produce sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the statutory directives allowing such intervention are fully satisfied." In re N.H., op. Cit. At 235; In re J.M., op. Cit. At 607.

Therefore, it is the burden and heavy responsibility of the State to demonstrate by sufficient evidence, not generalized assumption, that it is necessary to separate each of these 112 children from his or her parents. 33 V.S.A. §631 (a) (3).

(D.)

The State virtually admits that it cannot meet this burden. It's Petition, on its face, does not even allege that the children are, indeed, in need of care and supervision. The allegation is merely a blatantly generalized assumption that "all children under the age of 18 residing in the Community of the Northeast Kingdom Community Church (NEKCC) in Island Pond … may be in need of care and supervision …" (emphasis supplied).

Moreover, the State admits that there is not a single piece of evidence in the material submitted that documents a single act of abuse or neglect with regard to any of the 112 children.

The theory is that there is some evidence of some abuse at some time in the past of some other children in the community. The same, of course, may be shown of Middlebury, Burlington, Rutland, Newport or any other community. Such generalized assumptions do not warrant mass raids by the police removing the children of Middlebury, Burlington, Rutland, Newport or any other community (even a small, unpopular one).

Adlai Stevenson once quoted that "guilt is personal", and I might add "not communal". Our Court has held many times that mere presence at a particular place is not sufficient to establish participation in a particular act. See, e.g., State v. Wood, 143 Vt. 408, 411 (1983); State v. Carter, 138 Vt. 264, 269 (1980); State v. Orlandi, 106 Vt. 165, 171 (1934).

Therefore, "when the court seeks to take the child out of [the] parental home, it may do so only upon convincing proof." In re Y.B., 143 Vt. 344, 347 (1983) [Billings, C.J.]. Here, the State lacks any proof whatsoever as to these children and these parents, much less "convincing proof". "The right of children and parents to relate to each other free from government interference is a basic liberty … and will only be interfered with upon requisite proof of parental unfitness." In re Y.B., op. Cit. At 348. One's right to the care, custody and control of one's children is a fundamental liberty interest protected as well by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. In re C.L., 143 Vt. 554, 557-58 (1983); Santosky v. Kramer, 455 U.S. 745, 753 (1982).

These concerns apply at the detention stage of juvenile proceedings. "In cases of juvenile detention it is important .. to minimize the possible intrusion upon the parents' constitutional right to family integrity." In re R.S., 143 Vt. 565, 569 (1983) [Gibson, J.].

For these reasons this Court refused the State's rather incredible request that the Court issue a blanket detention order for 112 children ex parte and without even holding hearings. The same reasons compelled denial of that request after holding the adversary hearings.

(E.)

Indeed, it is all too clear that the State's request for the protective detention permitted by the statute upon an appropriate showing was entirely pretextual. What the State really sought was investigative detention.

In effect, each of the children was viewed as a piece of potential evidence. It was the State's admitted purpose to transport each of the 112 children to a special clinic where they were to be examined by a team of doctors and psychologists for evidence of abuse. If no signs of abuse were found, a child would be returned to its parents provided the parents "cooperated", that is, gave certain information to the police.

Thus, not only were the children to be treated as mere pieces of evidence, they were also to be held hostage to the ransom demand of information from the parents.

This stated plan of the State lends credence to the complaint of a number of the parents during the course of the hearings to the effect that they had been told by law enforcement personnel at the time of the raid that they would not be reunified with their children unless they gave certain information. During the course of the hearings the State did indicate that, if custody were awarded, children would be returned to "cooperative parents".

Had the Court issued the detention orders requested by the State it would have made itself a party to this grossly unlawful scheme.

In our society, people are not pieces of evidence. Such a "contention … clashes with a fundamental written into our Constitution …; no human being in the United States may be [so] dealt with … by government officials, or by anyone else." Blackie's House of Beef, Inc. v. Castillo, 467 F.Supp. 170 (D.C. 1978). Our rules relating to the issuance of search warrants reflects this basic concept. Such a warrant may be issued for a person only if there is probable cause to arrest that person, V.R.Cr.P. 41 (b) (5), or for a person who has been kidnapped or unlawfully imprisoned or restrained. V.R.Cr.P. 41 (b) (4).

Were it otherwise, the State could use the device of a search warrant or other detention to compel a traumatized rape victim to submit to physical and psychological examination in order to provide the State with evidence. Our society and laws would not for a moment countenance such an outrage. Yet, that is precisely how the State here proposes to treat these 112 children.

As for that part of the scheme that would return the children to "cooperative parents", such practices are disapproved "because of society's abhorrence of techniques of coercion". Whitebread, Constitutional Criminal Procedure, 163. Statements may not be obtained by means of physical brutality, Brown v. Mississippi, 297 U.S. 278 (1936); Williams v. United States, 341 U.S. 97 (1951), nor by psychological pressures. Spano v. New York, 360 U.S. 315 (1959).

No person may be held "in order that he may be at the disposal of the authorities while a case is discovered against him." In re Davis, 126 Vt. 142, 143 (1966). Neither may his child.

(F.)

Upon a proper evidentiary showing of abuse, this Court is not the lest reticent to take immediate and affective action under the law to protect the children who are the objects of such abuse.

Even such a goal as avoiding the abuse of children, however, cannot justify the means here employed.

The request for the detention orders were properly DENIED.

Dated this 25th day of June, 1984.

[Signed] Frank G. Mahady, District Judge

STATE OF VERMONT

ORLEANS COUNTY, ss.

IN RE: CERTAIN CHILDREN

DISTRICT COURT OF VERMONT

UNIT NO. 3, ORLEANS CIRCUIT

DOCKET NO.

OPINION: PHOTOGRAPHS

At dawn on June 22, 1984, 112 children were taken into custody by the State in Island Pond, Vermont. The authorities thereupon took three photographs of each child. One photograph of each child was attached to the return of custody form presented to the Court; one photograph of each child was retained by the police; one photograph of each child was given to Social and Rehabilitation Services.

During the course of hearings held on June 22, 1984, this Court ordered from the bench that all three photographs of each of the 112 children be delivered to the Court and sealed no later than the close of business on Monday, June 25, 1984. The Court at that time indicated that this Opinion regarding that order would subsequently be filed.

(A.)

The controlling statute is clear: "no photograph shall be taken of any child when taken into custody without the consent of the judge." 33 V.S.A. §664(e).

The State represents that they requested such consent from Hom. Judge Wolchik during an ex parte hearing prior to June 22. The Judge, according to the State, refused to specifically give such consent but indicated that the law enforcement authorities could "do whatever was necessary" to identify the children.

That hearing was tape recorded and no transcription of that tape has yet been made available. A transcript is not necessary to a proper disposition of the issue.

This court finds it difficult, if not impossible to believe that any judicial officer would issue such a sweeping delegation of his Constitutional duties to law enforcement authorities.[1] This Opinion, however, for the sake of argument, will proceed on the assumption that such an unprecedented delegation did, in fact, occur. That assumption avails the State not at all.

(B.)

First, such a sweeping indication to "do whatever was necessary" to identify the children is simply that - an "indication". It clearly is not the specific consent to photograph a specific child under specific circumstances for specific good cause shown which is contemplated by the statute, 33 V.S.A. §664 (e.).

When construing a statute, it is necessary to consider the statute's subject matter, effects and consequences as well as the spirit and reason of the law. State v. Teachout, 142 Vt. 69 (1982); Langrock v. Department of Taxes, 139 Vt. 108 (1980). The real meaning and purpose of the legislature should be determined and put into effect. State v. Mastaler, 130 Vt. 44 (1971); see, Philbrook v. Glodgett, 421 U.S. 707 (1975). This statute unmistakably intends to prohibit the taking of photographs of children taken into custody without specific judicial consent. There was none here.

(C.)

Second, it is all too apparent that the law enforcement authorities exceeded even the very broad consent they claim was obtained from Judge Wolchik.

That consent was conditioned upon the action taken being necessary to identify the children. A majority of the children taken into custody and their parents identified themselves by name to the police. Yet, all 112 children were photographed. Obviously, there was absolutely no need to photograph the majority of the children to identify them.

This fact alone illustrates the evil of such broad delegation of judicial authority to law enforcement. At best, the police went about taking pictures with unrestrained zeal; at worst, there is an ulterior motive behind the taking of the photographs.

(D.)

Third, such a delegation of judicial authority to law enforcement is constitutionally invalid under Vermont's separation of powers doctrine. The legislature has specifically provided that it is for the judiciary to determine whether a photograph of a specific detained child should be taken. 33 V.S.A. §664 (e).

Our Constitution leaves no room for doubt as to such a fundamental issue: "the Legislative, Executive, and Judiciary departments shall be separate and distinct, so that neither exercise the powers properly belonging to the others." VT. CONST., Ch. II, sec. 5.

The Executive, therefore, may not exercise the powers properly belonging to the Judiciary under 33 V.S.A. §664 (e).

Nor may the Judiciary effectively delegate such power to the Executive. It is a fundamental principle of the American Constitutional system, clearly expressed in Vermont's own State Constitution (Ch. II, sec. 5), that the legislative, executive and judicial departments of government are separate from each other, and therefore such functions of one department as purely and strictly belong to that department cannot be delegated, but must be exercised by it alone. State v. Auclair, 110 Vt. 147, 162 (1939) [Moulton, C.J.]; Village of Waterbury v. Melendy, 109 Vt. 441, 448 (1938).

Even were this one of those situations where necessity dictates some delegation, which it is not, any such delegation must not be unrestrained and arbitrary; it is essential that even permissible delegation establish certain basic standards, definite and certain policy, and rules of action. State v. Auclair, op. Cit. Qt 163. A delegation to "do whatever is necessary", on its face, fails woefully to establish any such standards, policies or rules.

(E.)

Fourth, the Fourteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution precludes such unrestrained delegation of authority to the police. It is not for them to determine "whatever is necessary" for them to do. As Mrs. Justice O'Connor has recently noted, there must be "minimal guidelines to govern law enforcement" and it is not permissible to allow "a standardless sweep that allows policemen [and] prosecutors … to pursue their personal predilections." The present cases illustrate all too well Mrs. Justice O'Connor's concern that such a situation "furnishes a convenient tool for harsh and discriminatory enforcement by local prosecuting officials against particular groups deemed to merit their displeasure" as well as her concerns centering upon "the potential for arbitrarily suppressing First amendment liberties." Kolender v. Lawson, 461 U.S. _____, 103 S.Ct. 1855 (1983).

The delegation of judicial authority claimed by the State to have been made here is so broad as to violate due process rights. It provided law enforcement authorities the power to do "whatever was necessary" to identify the children. Taken literally, it would allow the tattooing of numbers on the arms of the children for the purpose of later identification. In fact, many of the fears so well expressed by Mrs. Justice O'Connor in Kolender came home to roost in Island Pond on June 22, 1984.

The photographs of the children were taken without legitimate authority.

Dated this 25th day of June, 1984.

[Signed] Frank G. Mahady, District Judge

Endnotes:

- Indeed, it is of interest to note that Judge Wolchik's Order of June 21, 1984 contains absolutely no reference whatsoever to any such matters.

STATE OF VERMONT

ORLEANS COUNTY, ss.

IN RE: CERTAIN CHILDREN

DISTRICT COURT VERMONT

UNIT NO. 3 / ORLEANS CIRCUIT

DOCKET NO.

OPINION: DISMISSALS

On June 22, 1984, the State brought 112 children who had been taken into custody in Island Pond, Vermont, before this Court pursuant to 33 V.S.A. §640(2). The Court refused to grant orders of detention under 33 V.S.A. §641 as to any of the children. The Court also dismissed the State's Petition as to 45 children.

At the time of the dismissals from the bench, the Court indicated that this Opinion would subsequently be filed.

(A. )

In each case that was dismissed, the State was unable to furnish the Court with the name of the child or the name and residence of the child's parent, custodian or guardian as required by 33 V.S.A. §646(2).

Of course, under certain circumstances "John Doe" juvenile petitions may be appropriate. The example of an abandoned infant comes immediately to mind. Clearly, the Legislature adopting 33 V.S.A. §646(2) did not intend the irrational result of precluding State action under such circumstances.

However, under the circumstances presented to this Court on June 22, the State's own theory of the case ran obviously afoul of both the First Amendment and the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The State argued its case well and clearly. Its theory was that there was considerable evidence of the abuse of some children in the past by some members of the Northeast Kingdom Community Church in Island Pond.

The Deputy Attorney General and the Special Assistant Attorney General both stated to the Court that there was no evidence whatsoever of any specific acts of abuse directed toward any one of the 112 children brought before the Court.

To close this obvious probable cause gap, the State argued that the 112 children were found in residences or other buildings owned by the church and that it was a basic tenet of the church to harshly discipline children. The argument concluded that each of the 112 children "may be in need of care and supervision."

Therefore, the essential causal nexus in the State's position was the association of each child's parent, custodian or guardian with the church in the face of the church's tenet teachings regarding child discipline.[1]

(B.)

This reasoning fails logically with its first assumption. That assumption is that the children and custodians found within the buildings of the church are associated with the church.

Simple logic dictates that the conclusion does not necessarily follow from the premise. In fact, the hearings held on June 22 demonstrated the opposite. By way of example, the State's dragnet ensnared not only church members but also at least three children from Rutland County, one child from Massachusetts, and one thoroughly annoyed lawyer from Hardwick.

With regard to the cases dismissed, this Court could not in good conscience ignore this gaping hole in the State's case as to children and custodians whom the State could not even identify much less associate with the church and its tenets. The law is absolutely clear that mere presence at a particular place is not sufficient to establish participation in a particular act. See, e.g., State v. Wood, 143 Vt. 408, 411 (1983); State v. Carter, 138 Vt. 264, 269 (1980); State v. Orlandi, 106 Vt. 165, 171 (1934).

(C.)

Even were the State able to overcome this threshold problem, it would be met by yet more fundamental obstacles. If we assume for the purpose of argument that each child was under if the control of a parent, custodian or guardian associated with the church, and that it is a tenet of the church to harshly discipline children, simple logic again dictates that the conclusion that each such child has been illegally disciplined does not follow. (Many Catholics, for example, exercise birth control.)

Even were the Court to ignore this logical flaw in the State's position, the probable cause argument offends (1.) the Fifth Amendment in that it impermissibly imputes guilt to an individual merely on the basis of his associations rather than because of some concrete personal involvement; see, e.g., Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U.S. 500 (1964), and (2.) the First Amendment in that it infringes on the free exercise of religion and association, see, e.g., United States v. Robel, 389 U.S. 258 (1967). Such basic and fundamental concerns the Court cannot ignore.

(D.)

As Mr. Justice Harlan has said, "in our jurisprudence guilt is personal" and where the government attempts to impute conduct to an individual by reason of that individual's associations "that relationship must be sufficiently substantial to satisfy the concept of personal guilt in order to withstand attack under the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment." Scales v. United States, 367 U.S. 203, 224-25 (1961).

Moreover, "the First Amendment guarantees freedom of association with religious and political organizations, however unpopular. Thus, the government cannot punish an individual for mere membership in a religious or political organization that embraces both illegal and legal aims unless the individual specifically intends to further the group's illegal aims." United States v. Lemon, 723 F.2d 922, 939 (D.C. Cir. 1983).

Therefore, in such cases, "there must be clear proof that a [person] specifically intends to accomplish [the illegal aims of the organization]." Scales v. United States, op. cit. at 229 (emphasis supplied); Noto v. United States, 367 U.S. 290, 2109 (1961). The test is well-established: the State must not only establish that the individual is a member of an organization embracing illegal aims; it must also show by clear proof that such a person is an active member of such an organization and that he or she specifically intends to carry out such illegal aims. Hellman v. United States, 298 F.2d 810, 812-13 (9th Cir. 1962); United States v. Lemon, op. cit. at 939-40; United States v. Robel, op. cit.; Elfbrandt v. Russell, 384 U.S. 11 (1966); Aptheker v. Secretary of State, op. cit.; Scales v. United States, op. cit.

Here, where the State cannot even identify the individual parent, custodian or guardian, it fails entirely to meet its Constitutionally mandated burden. Compare, e.g., United States v. Robel, op. cit.

(E.)

While most of the cases involving these First and Fifth Amendment issues have dealt with the validity of criminal statutes, "the Court has consistently disapproved governmental action imposing criminal sanctions or denying rights and privileges solely because of a citizen's association with an unpopular organization." Healy v. James, 408 U.S. 169, 185-86 (1973) [emphasis supplied]; NAACP. v. Claiborne Hardware Co., 458 U.S. 896, 919 (1982).

These Constitutional principles, for example, have been applied to the government's right to revoke a passport, Aptheker v. Secretary of State, op. cit., to regulate admission to the bar, Baird v. State of Arizona, 401 U.S. 1 (1971), and to deny public employment. Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S 589 (1967). Clearly, they apply to the fundamental liberty interest in one's right to the care, custody and control of one's children which is protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In re C.L., 143 Vt. 554,557-58 (1983), Santosky v. Kramer, 455 U.S. 745, 753 (1982).

(F.)

This is not to ignore the fact that the State demonstrates a legitimate and compelling interest. It does. The problem of child abuse is a grave one to which this Court has given substantial attention. It is one of our most serious societal problems. It is, therefore, entirely proper and, indeed, desirable for the State to attack it aggressively. In short, the State's motives are not at issue.

Mr. Chief Justice Warren in Robel wrote, "however, the phrase 'war power' cannot be invoked as a talismanic incantation to support any exercise of congressional power which can be brought within its ambit." United States v. Robel, op. cit. At 263. Likewise, the phrase "child abuse" cannot be invoked as a talismanic incantation to support the exercise of State power which egregiously violates both First and Fifth Amendment rights. Even where the State acts in a noble cause, it must act lawfully.

There was no probable cause for the Petition as applied to the facts of the cases dismissed. They were therefore properly DISMISSED.

Dated at Middlebury, Vermont this 2nd day July, 1984.

[Signed] Frank G. Mahady, District Judge

Endnotes:

- The same analysis applied to the State's allegations of truancy and lack of proper medical care.

STATE OF VERMONT

ORLEANS COUNTY, ss.

IN RE: CERTAIN CHILDREN

DISTRICT COURT OF VERMONT

UNIT NO. 3, ORLEANS CIRCUIT

DOCKET NO. 22-6-840sj

OPINION AND ORDER: PETITION

The parents have moved to dismiss the Petition in this proceeding. The Motion was heard at North Hero, Vermont, on July 12, 1984.

The State has filed eight Amended Petitions. This Opinion and order does not address those Amended Petitions. Hearings on the Motion to Dismiss will be held separately on each such petition at a time to be scheduled by the Clerk.

(I)

A.

In Vermont, the juvenile court has "exclusive jurisdiction over all proceedings concerning any child who is or who is alleged to be... a child in need of care or supervision... 33 V.S.A. §633(a). This jurisdiction is invoked by the filing of a petition: "Upon the request of the commissioner of social and rehabilitation services... the State's Attorney[1] having jurisdiction shall prepare and file a petition alleging that a child is in need of care and supervision." 33 V.S.A. §645(a). The petition must be verified. 33 V.S.A. §646.

Such a petition "shall set forth plainly the facts which bring the child within the jurisdiction of the court...

The petition here (excluding from consideration the eight amended petitions subsequently filed) nowhere alleges that any of the children are children in need of care and supervision. The only allegation is a blatantly generalized assumption that "all children under the age of 18 residing in the community of the Northeast Kingdom Community Church (NEKCC) may be in need of care and supervision" (emphasis supplied). This simply does not meet the requirements of the statutes that the State's Attorney (or, presumably the Attorney General) set forth in a verified petition that a child brought before the Court "is or is alleged to be a child in need of care or supervision."

The State attempts to avoid this responsibility by pointing to that part of the Petition which reads "therefore, your petitioner asks the Court to hear the petition and find that all children residing in the community of the NEKCC as designated above are in need of care and supervision." (emphasis supplied in State's Memorandum). Of course, the simple answer to this frankly sophistic argument it that there the State "asks", it does not "allege". The statutes require the State to make a verified allegation, not a prayer for relief.

Given the generalized assumptions upon which the State relies, and given the continuing admission of the State that it has no specific evidence of abuse, truancy or lack of adequate medical care as to any specific child or parent, it is not surprising that no attorney for the State apparently was willing to put his signature to a verified petition which actually alleged any of these children to be, in fact, in need of care and supervision.[2]

It is certainly inappropriate for the Judiciary to allow the Executive to circumvent the clear requirements .(particularly that of a verified allegation) set forth by the Legislature.

The Petition is defective on its face.[3] The defect is jurisdictional. 33 V.S.A. §633(a).

This defect underscores the fundamental difficulty with the State's attempted justification for these proceedings: it sought, through the juvenile proceedings, an investigative detention which, the State hoped, would provide proof to support the initiation of the juvenile proceedings. This puts the cart before the horse. Under our system of justice, the State must have an adequate factual basis upon which to act against individuals first; it cannot act first, then hope that the action itself will unearth proof to retroactively justify the action. In the context of this case, these are not easily corrected problems of technical pleading; they rather are difficulties of fundamental concern which go to the very heart of the matter.[4]

B.

On its face, the Petition gives no notice, or even indication, to the parents or to the juveniles as to the claims of the State which they will be required to meet. Cf, e.g., In re Anonymous, 37 Misc. 2d 827, 238 N.Y.S. 2d 792 (1962); In re Neal D., 100 Cal. Rptr. 706, 708-9 (1972).

The State attempts to save the Petition from this inadequate notice under due process standards through the use of the affidavit attached to the Petition and incorporated into the Petition by reference.

Of course, it is appropriate to read the petition in conjunction with the supporting affidavit. In re S.A.M., 140 Vt. 194, 197 (1981); In re T.M., 136 Vt. 427, 429 (1980); In re Certain Neglected Children, 134 Vt. 74, 77-78 (1975). However, in both In re S.A.M. and In re T.M., the Supreme Court has warned very clearly "that it would be better practice for the State to provide for specific allegations of the grounds relied on in its petition." See, also, In re A. D., 143 Vt. 432, 435 (1983). The State ignores such repeated warnings at its peril.

The basic problem, of course, is the State's admission that the affidavit contains no specific allegation or specific evidence of abuse, truancy, or lack of adequate medical care as to any specific child or parent. (Compare, by way of example, the opinion of Mr. Justice Peak in In re A.D., op. cit.)

In the present case, the Petition makes no attempt to allege facts constituting any of the children to be children in need of care or supervision. Although the accompanying affidavit does make reference to other specific children, presumably living in the same community, it is essentially a collection of generalized assumptions as to these children. There is no documented evidence before the Court that any of the children or parents are even active, participating members of that community. (Indeed, at the detention hearing, it was demonstrated that some were not.)

It is not required of each parent and each child to "sort out from the morass of claims" those allegations and generalized assumptions which may, somehow, relate to them. See, State v. Phillips, 142 Vt. 283, 289-90 (1982); compare, State v. Christman; 135 Vt. 59 (1977). Such a morass does not reasonably indicate to the parent or the juvenile the nature of the State's specific claim as to them nor does it provide a basis which would make possible intelligent preparation for a merits hearing.[5] See, Besharov, Juvenile Justice Advocacy, 189 et. seq. (1979).

Moreover, this morass does not come close to satisfying the statutory requirement that a juvenile petition "set forth plainly the facts which bring the child within the jurisdiction of the court." 33 V.S.A. §646 [emphasis supplied].

It is true that modern rules of pleading are designed to forgive the sloppy pleader. They do not, however, carry such forgiveness to the point of requiring adverse parties to guess what specific claims against them as individuals they will need to meet. "One of the stated purposes of Title 33, Ch. 12 is to assure a fair hearing and protection of the parties' constitutional and other legal rights." In re T.M., op. cit. at 429-30; 33 V.S.A. §631(a)(4); see, In re Lee, 126 Vt. 156, 158-59 (1966).

(II)

A.

The State has argued its case well and clearly. Its theory claims that probable cause exists because there is considerable evidence indicating the abuse of some children in the past by some members of the Northeast Kingdom Community Church in Island Pond. The State admits, however, that there is no evidence whatsoever of any specific acts of abuse or neglect as to any one of the children subject to the Petition.[6]

Attempting to close this obvious probable cause gap, the State argues: 1) it is a basic tenet of the church to use corporal punishment to discipline its children; and 2) that the children were found in residences or other buildings owned by the church and therefore must be members of the church subject to discipline. The argument concludes that each of the children is, therefore, "at risk" and "may be in need of care and supervision", based on "their environment".

The essential causal nexus in the State's position is the association of each child's parent, custodian or guardian with the church in the face of the church's tenet and teachings regarding child discipline. While the State prefers to describe its approach as an "environment theory", seen properly it is an "association theory". As such, it runs obviously afoul of simple logic as well as both the First Amendment and the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[7]

B.

The State's argument fails logically with its first assumption, i.e., that the children and custodians found within the buildings of the church are associated with the church.

Simple logic dictates that the conclusion does not necessarily follow from the premise. In fact, the hearings held on June 22 demonstrated the opposite. By way of example, the State's dragnet ensnared not only church members but also at least three children from Rutland County, one child from Massachusetts, and one thoroughly annoyed lawyer from Hardwick.

The law recognizes this simple logic and is absolutely clear: mere presence at a particular place is not sufficient to establish participation in a particular act. See, e.g., State v. Wood, 143 Vt. 408, 411 (1983); State v. Carter, 138 Vt. 264, 269 (1980); State v. Orlandi, 106 Vt. 165, 171 (1934).

Even were the State able to overcome this threshold problem, it would be met by another logical obstacle. If we assume for the purpose of argument that each child is under the control of a parent, custodian or guardian associated with the church, and further, that it is a tenet of the church to harshly discipline children, simple logic again dictates that the conclusion that each such child has been illegally disciplined does not follow. (Many Catholics, for example, exercise birth control.)

C.

Even were the Court to ignore these logical flaws in the State's position, the argument fundamentally offends 1.) the Fifth Amendment in that it impermissibly imputes guilt to an individual merely on the basis of his associations rather than because of some concrete personal involvement; see, e.g., Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U.S. 500 (1964), and 2.) the First Amendment in that it infringes on the free exercise of association see, e.g., United States v. Robel, 389 U.S. 258 (1967). Such basic and fundamental concerns the Court cannot ignore.

Mr. Justice Harlan has said, "in our jurisprudence guilt is personal"; where the government attempts to impute conduct to an individual by reason of that individual's associations, "that relationship must be sufficiently substantial to satisfy the concept of personal guilt in order to withstand attack under the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment." Scales v. United States, 367 U.S. 203, 224-25 (1961).

Moreover, "the First Amendment guarantees freedom of association with religious and political organizations, however unpopular. Thus, the government cannot punish an individual for mere membership in a religious or political organization that embraces both illegal and legal aims unless the individual specifically intends to further the group's illegal aims." United States v. Lemon, 723 F.2d 9.22, 939 (D.C. Cir. 1983).

Therefore, in such cases, "there must be clear proof that a [person] specifically intends to accomplish [the illegal aims of the organization]." Scales v. United States, op. cit. at 229 (emphasis supplied); Noto v. United States, 367 U.S. 290, 299 (1961). The test is well established: the State must not only establish that the individual is a member of an organization embracing illegal aims; it must also show by clear proof that such a person is an active member of such an organization and that he or she specifically intends to carry out such illegal aims. Hellman v. United States, 298 F.2d 810, 812-13 (9th Cir. 1962); United States v. Lemon, op. cit. at 939-40; United States v. Robel, op. cit.; Elfbrandt v. Russell, 384 U.S. 11 (1966); Aptheker v. Secretary of State, op. cit.; Scales v. United States, op. cit. The State presents no such evidence.

D.

While most of the cases involving these First and Fifth Amendment issues have dealt with the validity of criminal statutes, "the Court has consistently disapproved governmental action imposing criminal sanctions or denying rights and privileges solely because of a citizen's association with an unpopular organization." Healy v. James, 408 U.S. 169, 185-86 (1973) [emphasis supplied]; NAACP v. Claiborne Hardware Co., 458 U.S. 896, 919 (1982).

These Constitutional principles, for example, have been applied to the government's right to revoke a passport, Aptheker v. Secretary of State, op. cit., to regulate admission to the bar, Baird v. State of Arizona, 401 U.S. 1 (1971), and to deny public employment. Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 589 (1967). Clearly, they apply to the fundamental liberty interest in one's right to the care, custody and control of one's children which is protected by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In re C.L., 143 Vt. 554, 557-58 (1983); Santosky v. Kramer, 455 U.S. 745, 753 (1982).

E.

Child abuse is one of our most serious societal problems. It is, therefore, entirely proper and, indeed, desirable for the State to attack it aggressively.[8]

Mr. Chief Justice Warren in Robel wrote, "however, the phrase 'war power' cannot be invoked as a talismanic incantation to support any exercise of congressional power which can be brought within its ambit." United States v. Robel, op. cit. at 263. Likewise, the phrase "child abuse" cannot be invoked as a talismanic incantation to support the exercise of state power which egregiously violates both First and Fifth Amendment rights. Even where the State acts in a sphere appropriate to state action, it must act lawfully.[9]

Here, the State can establish probable cause only by adopting a theory of guilt by association. Such a theory is unlawful.

F.

The State argues that it need not establish "probable cause" but rather only "reasonable grounds". Whichever label is used, the State fails to meet its burden.

Mr. Justice Frankfurter once wrote that "it is not the function of the police to arrest, as it were, at large and to use, an interrogating process at police headquarters in order to determine whom they should charge." Mallory v. United States, 354 U.S. 449, 456 (1957). Likewise, it is not the function of the State to take children into custody, as it were, at large and to use physical and psychological examinations during detention in order to determine whom they should make the subject of juvenile petitions.

The very position of the State reveals the lack of probable cause or reasonable grounds. It attempted to justify its initial action on the ground that it was essential to proceed against the parents and the children by way of temporary detention precisely in order to obtain otherwise unavailable evidence sufficient to support the petition. This lack of intellectual consistency in the State's position with regard to the need for temporary detention when compared with its position in defense of the petition betrays the entire episode for what it was — a massive fishing expedition.

In Vermont, the law is absolutely clear: "The power... allocated to the State (in juvenile cases] is awesome indeed... Accordingly, any time the State seeks to interfere with the rights of parents on the generalized assumption that the children are in need of cart and supervision, it must first produce sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the statutory directives allowing such intervention are fully satisfied." In re N.H., 135 Vt. 230, 235 (1977) [Hill, J.]; In re J.M., 131 Vt. 604, 607 (1973). (emphasis supplied).

Here, there is presented, at best, mere generalized assumptions. The State, by its own admission, fails to "first present sufficient evidence to demonstrate" that any one of these specific children is in need of care and supervision. It is fundamental that the justification for the State to act with regard to any specific individual "must be ... particularized with respect to that person." Ybarra v. Illinois, 444 U.S. 85 (1979). Demonstrably, the State will be unable to establish the necessary facts to support its petition by a preponderance of the evidence. Compare, In re A.D., 143 Vt. 432 (1983). While State intervention pursuant to 33 V.S.A. §685 might well be justified (if not required) by the evidence available to the State, the filing of the petition was clearly premature.

The Petition, except as to the eight Amended Petitions, is DISMISSED.

Dated at Middlebury, Vermont, this 7th day of August, 1984.

[Signed] Frank G. Mahady, District Judge

Endnotes:

- The juveniles here re involved were found in the Town of Brighton. The Essex County State's Attorney has not appeared in this case, nor has the Court had any indication of his role (if any) or his position in this matter. There is no evidence that he withdrew or declined to take action as was the situation in State's Attorney v. Attorney General, 138 Vt. 10 (1979); however, it would appear that the holding in State's Attorney v. Attorney General would support the assumption of authority here by the Attorney General although the cases are arguably distinguishable.

- See, State v. Woodmansee, 128 Vt. 467, 472 (1970): "It is the law of the State of Vermont that a State's Attorney shall not set his hand to an official complaint, unless he has gone far enough... to satisfy himself of the probable guilt of the party to be charged."

- It also must be noted that the facially defective nature of the Petition was brought to the attention of the State by Justice Keyser on June 19, 1984, in the matter of In re Certain Children, Docket No. 1-6-84Ej.

- The State claims justification here under 33 V.S.A. §685. Of course, what was done here does not come close to the procedures set forth in Sec. 658. One can only be left to wonder why that statute was not utilized in the first instance. Such investiga-tive detentions involve "a massive curtailment of liberty", and even where specifically authorized by statute serious scrutiny must be given to the procedures surrounding them. See, In re W.H. ____Vt.____ (1984).

- In this regard, it is interesting to note that a number of highly skilled and experienced attorneys representing the children have indicated, as officers of the Court, that they are unable, on the basis of the pleadings, to even conduct meaningful initial interviews with their clients.

- The same analysis applies to the State's allegations of truancy and lack of proper medical care.

- Of course, the State's analogy to a community inflicted by an epidemic of a contagious disease does not share these difficulties.

- However, cases such as Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U.S. 158 (1944) and State v. Rocheleau, 142 Vt. 61 (1982) are hardly in point. The individual right and interest in the integrity of the family as well as the privacy expectation in one's own residence are far more important than the interest in a minor selling papers or the smoking of marijuana. Moreover, those cases are "free exercise" cases and would support the proposition that that clause of the First Amendment would not protect child abuse. With that proposition the Court emphatically agrees, but it is not here in issue.

- The State in a supplemental memorandum, filed out of time attempts to justify the Petition on the ground that the children have a due process right to State intervention. It relies upon a single trial court decision from South Carolina, Jensen v. Conrad, 570 F.Supp. 114 (D.C.S.C. 1983). The State, of course, has no standing to assert this right in the first instance. (Of interest in this regard is the fact that of 30 attorneys representing the interests of the children, not one saw fit to raise this issue on their behalf.) Moreover, Jensen at most requires the State to conduct a proper investigation. While the State may be required to take action, it must nevertheless do so properly and with a due regard for the rights of all involved.

STATE OF VERMONT

ORLEANS COUNTY, ss.

IN RE: CERTAIN CHILDREN

DISTRICT COURT OF VERMONT

UNIT 3, ORLEANS CIRCUIT

DOCKET NO. 22-6-840sj

OPINION AND ORDER: SEARCH WARRANT

The parents have moved to suppress evidence seized on June 22, 1984, by the Vermont State Police and social service agencies as well for the return of the property seized. The motion was heard at North Hero, Vermont, on July 12, 1984.

(I)

A.

The history of western civilization provides a foundation for analysis. It reveals an ancient and profound respect for the dwelling of an individual. It also illustrates the antiquity and importance of the requirement that the authorities must have cause to invade such dwellings and may do so only with specific and particularized authority.

Biblical literature provides many illustrations of this respect for a person's home which was not subject to arbitrary visitation, even on the part of official authority. By way of example, the King of Jericho in the face of enormous "social costs", sent messengers rather than a search party to the home of Rachab. Joshua, 2:1-7. Other examples may be seen at Gen, 19:4-11 and Joshua, 7:10-26. Under the ancient codes, even a baliff of the court could not enter a home to obtain security for a debt. See, 14 Rodkinson, The Babylonian Talmud, 113 (Boston, 1918).

The familiar maxim, "every man's house is his castle", is usually credited to Lord Coke. See, Coke, 5 Rep. 92. Actually, it derives from the Roman law: Nemo de domo sua extrahi debet. Digest of Justinian, 50. Cicero, in one of his orations, declares flatly, "What is more inviolable, what better defended...' than the house of a citizen... This place of refuge is so sacred to all men, that to be dragged from thence is unlawful." Verrine Orations; see, Radin, Roman Law (St. Paul, 1927). Of particular note, a Roman search warrant had to describe with particularity that which was sought. Mommsen, Römisches Strafrecht, 748 (Leipzig 1899). Mommsen quotes the following passage, highly relevant here, from Paulus: Qui Furtum quaesiturus est, antequam quaerat, debet dicere quid quaerat et rem suo nomine et sua specie designare. So cautious were the Romans that the execution of a warrant was ceremonial and done lance et licio that is, the searcher entered the home clad only in an apron (licio) bearing a platter in his hand (lance) in the presence of required witnesses as well as a court baliff and a public crier. Mommsen, op. cit. 749-49.

In Anglo-Saxon times, Alfred the Great (871-891) sentenced to death one who was responsible for "a false warrant, grounded upon false suggestion." Mirrour of Justices. 246 (Washington, 1903) [attributed to Horne, ca. 1290].

Therefore, Magna Carta, usually cited as the fountainhead of modern civil liberties, is relatively a historical newcomer. In the context of our Western civilization, the sense that the State conduct involved here seems to touch a raw antecedal nerve becomes more understandable.

By the seventeenth century, salutory rules, founded in this tradition, regarding the use of general warrants were being developed by the British common law. Chief Justice Hale (1609--1676), one of the greatest jurists in English history, see, 4 Holdsworth, History of the English Law, 574-95 (3rd ed.) [London, 1926], held a general warrant to apprehend all persons suspected of having committed a given crime to be void. 1 Hale, History of the Pleas of the Crown 580 (Philadelphia, 1897). He ruled that a warrant must specify by name or description the particular person or persons to be arrested and not be left in general terms or in blanks to be filled in afterwards. 2 Hale, op. cit., at 576-77. Likewise, Hale ruled that warrants to search any suspected place for stolen goods were invalid and should be restricted to search in a particular place suspected after a showing, upon oath, of the suspicion and the "probable cause" thereof, to the satisfaction of the magistrate; he concluded that "searches made by pretense of such general warrants give no more power to the officer...than what they may do by law without them." 2 Hale, op. cit. at 150.

In 1762, Lord Halifax's infamous general warrant directed against the allegedly seditious publication of John Wilkes, The North Briton, led to the landmark case of Wilkes v. Wood, 19 How. St. Tr. 1153, 98 Eng. Rep. 489 (1763). The warrant was held by Chief Justice Pratt to be illegal: "To enter a man's house by virtue of a nameless warrant," wrote the Chief Justice, "in order to procure evidence, is worse than the Spanish Inquisition; a law under which no Englishman would wish to live an hour."

Two years following the Wilkes decision, a warrant specifically naming John Entick and his publication, Monitor, was held invalid in that it provided for the seizure of Entick's "books and papers". Entick v. Carrington, 19 How. St. Tr. 1029 (1765). That opinion has been described as the "true and ultimate expression of constitutional law." Boyd v. United States, 116 U.S. 616, 626-27 (1886). In Entick, Chief Justice Pratt, who had become Lord Camden, said "this power so assumed by the ... state is an execution upon all the party's papers in the first instance. His house is rifled: his most valuable secrets are taken out of his possession, before the paper for which he is charged is found to be criminal by any competent jurisdiction, and before he is convicted either of writing, publishing, or being concerned in the paper." Entick v. Carrington, op. cit. at 1064.[1]

In the wake of Wilkes and Entick, the House of Commons adopted two resolutions condemning general warrants in England. 16 Hansard's Parliamentary History of England, 207; Lasson, The History and Development of the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution, 49 (1937). In the course of that debate, William Pitt made-his famous declaration:

The poorest man may, in his cottage, bid defiance to all the force of the Crown. It may be frail; its roof may shake; the wind may blow through it; the-storm may enter; the rain may enter; but the King of England may not enter; all his force dares not cross the threshold of the ruined tenement.

Quoted in Lasson, op. cit., at 49-50.

Likewise, the comments of James Otis, Jr., in the course of his unsuccessful 1761 defense of Boston merchant s against that form of general warrant known as the writ of assistance, had much to do with the advent of the American Revolution. One of those present at the trial, John Adams, later wrote, "Then and there the Child of Independence was born. In fifteen years, namely in 1776, he grew up to manhood, and declared himself free," 10 C. Adams, The Life and Works of John Adams, 247-48 (1856).

Against this history stands the State's argument that the search warrant here involved was valid, that the State's conduct was "reasonable" and that the State, in any event, acted upon an "objectively reasonable, good faith belief" in the warrant's validity. To ignore history is, indeed, to repeat its mistakes.

B.

Constitutional analysis must focus, in the first instance, upon the Vermont Constitution. As Mr. Justice Linde, of the Oregon Supreme Court, has said, "the states' bills of rights ar e first things that come first." Linde, "First Things First: Rediscovering the States' Bills of Rights", 9 Univ. of Balt. L.R. 379, 380 (1980).

Former Chief Justice Barney wrote that "a state court reaches its result in the legal climate of the single jurisdiction with which it is associated, if federal proscriptions are not transgressed," State v. Ludlow Supermarkets, Inc., 141 Vt. 261, 268 (1982). Whenever a person asserts a particular right, and a state court recognizes and protects that right under state law, there is simply no federal question. Therefore, "a state court should put things In their logical sequence and routinely examine its state law first, before reaching a federal issue." Linde, op. cit.

To first determine whether the state has violated the Federal Constitution and then, only when it has not done so, to reach a question under state law is to stand the Constitution on its head. Id. at 387; see, Falk, "Forward: The State Constitution — A More Than 'Adequate' Nonfederal Ground," 61 Cal. L.Rev. 273 (1973).

Mr. Justice Hill, in a significant opinion, declared that if our State Constitution is to mean anything, it must be enforced... Our duty to enforce the fundamental law of Vermont, our role in the federalist system, and our obligation to the parties...compel us to address the (issues) under the Vermont Constitution." State v. Badger, 141 Vt. 403, 449 (1982). It follows that "a state court should always consider its state constitution before the Federal Constitution. It owes its state the respect to consider the state constitutional issue." Linde, op. cit. at 383. "[T]he Vermont Constitution provides an independent authority . . . of equal importance with the federal charter.' State v. Badger, op. cit. (emphasis supplied). As such, Vermont's courts are "free ... to interpret the precise meaning of our own constitution... so long as no federal proscriptions are transgressed." In re E.T.C., 141 Vt. 375, 378 (1982) [Billings, J.].

In short, the Vermont courts are not bound to slavishly imitate the Federal judiciary. Were it otherwise, our great national experiment in federalism would be abandoned insofar as it applied to the judicial branch of government.

Of course, certain irreducible standards, as declared under the Federal Constitution from time to time by the United States Supreme Court, bind us as a nation. No state can choose to reject them. Neither are the people of any state, however, bound to be satisfied with the minimum standard allowed to all. Linde, op. cit. at 395.

In this regard, it is interesting to note that, during the months preceding our national Declaration of Independence, it was seriously debated that the Continental Congress should draft uniform constitutions for the states. This idea was rejected in favor of calling upon each state to write a constitution satisfactory to itself. See, Green, Constitutional Development in the South Atlantic States, 1776-1860, 52-6 (1930). To simply adopt federal decisions under the federal constitution when looking to a state constitution, then, is to compare apples with oranges. See, e.g., State v. Kaluna, 55 Hawaii 361, 369, n. 6, 520 P.2d 51, 58, n. 6 (1974).

It is therefore the duty of the Vermont courts to enforce Vermont's Constitution as an "independent authority and Vermont's fundamental law." State v. Badger, op. cit. Our state, free and independent,[2] has a proud recent history with regard to the performance of this duty. Ludlow, E.T.C., and Badger are illustrative. Indeed, "the Barney Court's recognition and application of distinct state constitutional standards has been cited as a major development in the jurisprudence of the fifty states." Billings, "Tribute to Chief Justice Barney, 8 Vt. L.Rev. 203, 205 (1983).

This Court, following the leadership of our Vermont Supreme Court, will take most seriously "the independent responsibility of (a] state court for the condition of liberty in [its] state." Linde, op. cit. at 379 (emphasis supplied).

Notes:

- See, also, Money v. Leach, 3 Burr. 1692, 97 Eng. Rep. 1050, (1765) [Opinion of Chief Justice Mansfield].

- "… [W]e will, at all times hereafter, consider ourselves as a free and independent state...." Ira Allen, Clerk, The Westminster Convention, January 15, 1777.

(II)

A.

The search warrant here involved purported to Authorize the search of 19 buildings in Brighton, Vermont, and one building in Barton, Vermont, for "the following evidence and people:

- any and all children under the age of 18 years old found herein [sic] except the children belong [sic] to Carl and Coleen Gamba; ...

- any and all rods or paddles;

- any and all medical supplies, indicative of the illegal practice of medicine;

- any and all photographs of discipline and/or illegal medical practices;

- any and all letters, tapes, writings or records involving the physical discipline of children, education of children, and/or illegal medical practices;...

A broader warrant can scarcely be imagined. It is for 20 separate buildings, most of which are residences. The authorization to seize "any and all children under the age of 18 years old" is broader in scope (though admittedly less Draconian in purpose than that of Herod the Great. The directive as to "any and all letters, tapes, writings or records" as well as "any and all photographs" is broader than those condemned by Lord Camden in Entick v. Carrington, 19 How. St. Tr. 1029 (1765) and by the United States Supreme Court in Stanford v. Texas, 379 U.S. 476 (1965).[1]

These four separate aspects (20 buildings, "all children", "all photographs", and "any and all letters, tapes, writings or records"), taken together, created a warrant more general in scope than any which this Court can find, after careful research in the recorded literature. It may, indeed, set a modern world record for generality; certainly, no competitor for that dubious title has made itself known.[2]

B.

The Vermont Constitutional Convention of 1777 included the following in our Bill of Rights:

... the people have a right to hold themselves, their houses, papers and possessions, free from search or seizure; and therefore warrants, without oath or affirmation first made, affording sufficient foundation for them, and whereby by any officer or messenger may be commanded or required to search suspected places, or to seize any person or persons, his, her or their property, not particularly described, are contrary to that right, and ought not to be granted. VT. CONST., Ch. I, Art. 11. (emphasis supplied).

It is no historical accident that this provision was adopted but ten years after the decision in Entick, op. cit., and only 12 years after the decision in Wilkes v. Wood, 19 How. St. Tr. 1153 (1763). These famous cases and the events leading up to them were obviously very much in the minds of those early Vermonters responsible for the adoption of Ch. I, Art. 11.[3]

It is significant that our Constitution was adopted in 1777. The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution was not concurred upon by the two Houses of Congress until September 26, 1789; it did not become effective until ratified by the necessary eleventh state, Virginia, on December 15, 1791, the year of Vermont's statehood.

The authors of Vermont's Constitution were not only aware of Entick and Wilkes; also "vivid in the memory of the newly independent Americans were those general warrants known as writs of assistance under which officers of the Crown had so bedeviled the colonists." Stanford v. Texas, op. cit. at 481. One need have but a passing knowledge of the lives of the Allen brothers and Thomas Chittenden to appreciate their views of such warrants and the need for a charter which specifically addressed such warrants in the clear and unmistakable language of VT. CONST., Ch. I, Art. 11.

Its obvious contrast to U.S. CONST., Amend. IV is instructive. The Vermont provision focuses very clearly upon searches made pursuant to a warrant; it does so more specifically and in greater detail than does the "warrant clause" of the Federal charter. Our fundamental law commands that a warrant relating to persons or property "not particularly described" is "contrary to... right, and ought not to be granted."

The very language of VT. CONST., Ch. It Art. 11, reinforced by the historical context of its adoption, unmistakably prohibits the use of general warrants.

C.

The search warrant here in question does not "particularly describe" the children, the photographs, the letters, the tapes, or the records to be seized; it is, therefore, beyond doubt made unlawful by VT. CONST., Ch. I, Art. 11.[4]

Its authorization to seize "all photographs" and "any and all letters, tapes, writings or records" is, if anything, broader than the warrant against Entick authorizing the seizure of his "books and records". It is sobering, indeed, to find a 1765 decision so directly in point. However, it is known that the framers of Ch. I, Art. 11, had Lord Camden's decision very much in mind. The warrant is illegal. Entick v. Carrington, 19 How. St. Tr. 10.29 (1765).

As to the authorization to seize "all children under the age of 18 it is equally sobering to find the Seventeenth Century precedent of Lord Hale very much in point: a warrant must specify by name or description the particular person to be taken into custody and not be left to general terms or in blanks to be filled in later. 2 Hale, 576-77. of course, that is precisely what this warrant purported to allow. It was unlawful in Hale's time; it is no less so now.[5]

A part of the common law familiar as well to the framers of the Vermont Constitution was the rule that "searches made by pretense of...general warrants give no more power to the officers... than what they may do by law without them." 2 Hale, 150. Therefore, it follows that the searches and the seizures here in question were, in effect, conducted under no warrant at all within the obvious contemplation of VT. CONST., Ch. I, Art. 11. Under that provision, the obvious violations of our fundamental law "strip-the officer of all legal justification and stamps his search and seizure as illegal from the beginning." State v. Pilon, 105 Vt. 55, 57 (1933) [Powers, C.J.].

The Vermont Supreme Court has specifically hold that the precedents of Entick and Wilkes, representing the reasoning and conclusions "of the greatest courts of the English speaking nations", are incorporated into the "not particularly described" provisions of VT. CONST., Ch. I, Art. 11. State v. Slamon, 78 Vt. 212, 213-14 (1901) [Taft, C.J.].

Suppression under Art. 11 is required. State v. Badger, 141 Vt. 430 (1982); State v. Slamon, op. cit. at 215.

(III)

A.

The State would have this Court graft onto the Vermont exclusionary rule a so-called "good faith" exception similar to that recently adopted by the United States Supreme Court in United States v. Leon, ____ U.S. ____, 35 Cr.L.R. 3273 (July 5, 1984) and Massachusetts v. Sheppard, ____ U.S. ____, 35 Cr.L.R. 3296 (1984). This is clearly not allowed under VT. CONST., Ch. I; Art. 11.

The Vermont exclusionary rule is entirely independent of the Federal rule under the Fourth Amendment as announced by the United States Supreme Court in Weeks v. United States, 232 U.S. 383 (1914). Its roots go deeper, and its rationale is different.

Vermont's seminal case dates back to 1802 when our Supreme Court invalidated an arrest for failure to comply with the warrant requirement of VT. CONST., Ch. I, Art. 11. State v. J.H., 1 Tyl. 444, 448 (1802). Not only was J.H. decided some 112 years prior to Weeks; of more significance, it was decided only 25 years after the adoption of Art. 11 in 1777.

In 1901, our Court specifically held that evidence seized in violation of Art. 11 is "inadmissible under Art. 10 of the Declaration of Rights." State v. Slamon, 73 Vt. 212, 215 (1901). Chief Justice Taft, noting the correctness of the ruling to be "clearly manifest" reasoned that "the seizure of a person's private papers to be used in evidence against him is equivalent to compelling him to be a witness against himself and... is within the constitutional prohibition." Id. (emphasis supplied).

This rationale differs entirely from that ascribed to the Federal rule by Mr. Justice White in Leon.[6] It follows that the reasoning of Leon is totally irrelevant to an analysis of the Vermont rule.

While there was a subsequent retreat from our rule, see, e.g., State v. Krinski, 78 Vt. 162 (1905), State v. Stacy, 104 Vt. 379 (1932), and State v. Cocklin, 109 Vt. 207 (1938), it is clear that "the positions adopted in cases such as State v. Krinski... have now been unequivocally repudiated." State v. Badger, op. cit. at 452. (emphasis supplied).

Statements obtained in violation of VT. CONST., Ch. I, Art. 10, were suppressed in State v. Miner, 128 Vt. 55 (1969) and in State v. Hohman, 136 Vt. 341 (1978). See, also, In re E.T.C., 141 Vt. 375 (1982).

The rule was applied, not only to the products of an illegal arrest but also to the indirect products of that arrest as well under VT. CONST., Ch. I, Art. 11 in State v. Dupaw, 134 Vt. 451 (1976) [Smith, J.]. There, the Court noted that "to effectuate the fundamental guarantees provided by ... the Eleventh Article of our State Constitution, we feel that the exclusionary prohibition should be extended to cover the indirect as well as the direct products of the unlawful arrest." Id. at 453.

Most recently our Court emphatically distinguished Art. 11's exclusionary rule from that of the Fourth Amendment as it was to be viewed by the Leon majority. State v. Badger, op. cit. On July 12, 1982, the Court unanimously cited with approval the leading scholarly article vigorously attacking the so-called "good faith" exception which the State would have us read into Art. 11, Mertens and Wasserstrom, "Forward: The Good Faith Exception to the Exclusionary Rule: Deregulating the Police and Derailing the Law". 70 Geo. L.J. 365 (1981). State v. Badger, op. cit. at 453.

More important, Mr. justice Hill's historic opinion specifically spelled out the reasons behind Art. 11's exclusionary rule. He noted that the "[i]ntroduction of such evidence at trial [1.] eviscerates our most sacred rights, [2.] impinges on individual privacy, [3.] perverts our judicial process, [4.] distorts any notion of fairness, and [5.] encourages official misconduct." Id.

Of these, the fifth and last alone is seen as being involved in the federal exclusionary rule by the Leon majority. The entire rationale of Leon is therefore addressed only to the conceptually narrower rule of the Fourth Amendment and has no relevance or meaning to the broader rule of Art. 11. Moreover, the Leon rationale does not address the reasoning of the Vermont Court in Slamon. There are at least six separate jurisprudential bases for Vermont's exclusionary rule; Leon is relevant to only one.

Badger held that it was the "introduction of such [illegally-obtained] evidence" which eviscerated sacred rights, impinged on privacy, perverted judicial process and distorted any notion of fairness. These results accrue whether or not good faith is involved on the part of law enforcement authorities. At the time of introduction (as opposed to the time of the search), the judicial process is perverted by means of the Court's use of such illegal evidence; at the time of introduction, there is a further invasion of privacy; at the time of introduction, fairness is distorted; at the time of introduction, basic rights are eviscerated. All of these results are recognized and precluded by Ch. I, Art. 11.

Even as to the encouragement of official misconduct, Leon is not persuasive authority. Under the unique facts of this case, there can be little doubt that state law enforcement and social welfare authorities would view an allowance of the use of the fruits of these searches to be a virtual blank check from the judiciary; conversely, there can be little doubt that exclusion will deter such massive systemic disregard for individual rights in the future.

Moreover, Leon is a tentative and experimental precedent. This is explicitly recognized by two members of the Leon majority. See, United States v. Leon, ____ U.S. ____, 35 Cr.L.R. 3273, 3281 (1984) where Mr. Justice Blackmun (concurring) noted "the unavoid-ably provisional nature of today's decisions" and the comment of Mrs. Justice O'Connor that "our conclusions concerning the exclusionary rule's value might change" in Immigration and Naturalization Service v. Lopez-Mendoza, ___ U.S. ___, 35 Cr.L.R. 3310, 3316 (1984).

If the doctrine of stare decisis is to mean anything in Vermont Constitutional law, certainly our Court will not abandon the recent, clear and well reasoned precedent of Badger required by our Constitution to join such a questionable experiment.[7]

There is no "good faith" exception available to the State under Ch. I, Art. 11 of the Vermont Constitution.

B.

Even were it necessary to resolve this issue under the Fourth Amendment of the Federal Constitution, the recently announced "good faith" exception to its exclusionary rule would not avail the State.

Mr. Justice White, in setting forth the new rule specifically held that it would not apply under certain circumstances. one of these is where "a Warrant may be so facially deficient — i.e., in failing to particularize the place to be searched or the things to be seized — that the executing officers cannot reasonably presume it to be valid." United States v. Leon, ___U.S.___, 35 Cr.L.R. 3273, 3280 (1984); compare, Massachusetts v. Sheppard, U.S. 35 Cr. L.R. 3296 (1984).

Therefore, the "good faith" exception of Leon explicitly does not apply to general warrants. It has already been demonstrated that the search warrant here at issue is a general warrant.

C.

The State further argues that suppression is not appropriate to a juvenile court proceeding. However, in Vermont, evidence obtained by means of an unlawful search and seizure "shall not be admissible in evidence at any hearing or trial." V.R.Cr.P. 41(e) (emphasis supplied). This Rule specifically applies to juvenile proceedings. V.R.Cr.P. 54(a)(2).

While this proceeding may not be "criminal", it is clear that a fundamental liberty interest worthy of constitutional protection is involved. In re C.L., 143 Vt. 554, 557-58 (1983); Santosky v. Kramer, 455 U.S. 745, 753 (1982); see, In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967).

The first four of the five purposes of Vermont's exclusionary rule set forth in State v. Badger, op. cit., all apply with equal force to juvenile proceedings and to criminal proceedings. The introduction of such evidence, by way of example, perverts the judicial process fully as much in a juvenile court as it does in a criminal court. This is clearly recognized by Rules 41 (e) and 54 (a) (2).

Moreover, as has been previously noted, the purpose of discouraging systemic, official misconduct must be central to this particular case. Given the fundamental liberty interests involved, the social welfare agencies and the police must not be allowed to perceive that they are being given a blank check with regard to juvenile proceedings. The Vermont judiciary owes its own Constitution the respect of ensuring that no mixed message is sent to these authorities. Application of the exclusionary rule to these proceedings is essential if meaning in the real world to the widely-recognized liberty interests involved in the juvenile court. See, Tirado v. C.I.R., 689 F.2d 307 (2nd Cir. 1982).

Even the recent opinion of Mrs. Justice O'Connor in INS v. Lopez-Mendoza, op. cit., relied upon by the State, supports this conclusion. Juvenile authorities do not routinely face the "mass detention" situation experienced by the INS agents; there is no comparable liberty interest involved in deportation proceedings; there is no showing that Vermont social welfare agencies or, for that matter, its State Police, have any comprehensive scheme for deterring constitutional violations such as exist at INS; and our juvenile proceedings are not in the least comparable to INS's deliberately simple deportation system. Under the circumstances of this case, Mr. Justice White's dissenting comment in Lopez-Mendoza would be even more obvious: " ... we neglect our duty when we subordinate constitutional rights to expediency in such a matter. 35 Cr.L.R. 3310, 3316, 3318.

Therefore, the exclusionary rule of Ch. I, Art. 11 applies to juvenile proceedings. V.R.Cr.P. 41(e) and 54(a)(2); see, State v. Badger, op. cit.; In re T.L.S., 139 Vt. 197 (1981). Were it necessary to apply the Fourth Amendment, its exclusionary rule would also be applicable. Compare, INS. v. Lopez-Mendoza, op. cit.[8]

D.

The case law relative to administrative searches applies only in "certain carefully defined classes of cases." G.M. Leasing Corp. v. United States, 387 U.S. 528-29 (1977). The State's attempt to apply that line of authority here is not appropriate.

Administrative searches of private residences, Camara v. Municipal Court, 387 U.S. 523 (1967) and of commercial buildings See v. Seattle, 387 U.S. 523, 534, constitute a "significant intru-sion upon the interests protected by the Fourth Amendment." Nevertheless, a special balancing test is sometimes applied to such routine searches "because the inspections are neither personal in nature nor aimed at the discovery of evidence of crime, [and] they involve a rather limited invasion of the urban citizen's privacy." Camara v. Municipal Court, op. cit. at 537.

Here, the search was hardly routine. The searches were intensely personal in nature and clearly aimed, among other things, at the discovery of evidence of crime. The massive invasion of privacy, was, of course, extreme. Compare, Michigan v. Tyler, 436 U.S. 499 (1978).[9]

The State attempts in its memoranda to justify the warrant as an administrative warrant and/or as a search warrant relating to evidence of a crime. However, the State never picks a horse and rides it to the finish line. As expediency dictates, the State's position shifts from "administrative" to "criminal" analysis depending upon which most nearly fits the State's position on any given issue. The resultant inconsistencies and lack of clear analysis are blatant.

(IV)

A.

Not only is the warrant facially defective being a general warrant. It was also issued without particularized probable cause.

A search warrant may be issued only upon "oath or affirmation first made, affording sufficient foundation." VT. CONST., Ch. I, Art. 11. Probable cause must exist before such a warrant may be issued. See, State v. Stewart, 129 Vt- 175 (1971).

"Where the standard is probable cause, A search ... must be supported by probable cause particularized with respect to that person." Ybarra v. Illinois, 444 U.S. 85 (1979) (emphasis supplied]. Therefore, "a person's mere propinquity to others independently suspected of criminal activity does not, without more, give rise to probable cause to search that person…." Id.

Here, the State admits that it had no specific evidence of abuse, truancy or illegal medical practices on the part of any of the individuals whose residences were searched. It relies, instead, upon the mere assumed association of these residences with some other people for whom there was some reason to suspect such activities at some time in the past.

This theory stretches probable cause to dwellings on the basis of the "mere propinquity" of the structures to others.

Moreover, as is demonstrated elsewhere, the State's "environment theory" is, in truth, an "association theory" violative of the Due Process clause of the Fifth Amendment and the Association Clause of the First Amendment. [See this Court's "Opinion and order; Motion to Dismiss", filed concurrently with this Opinion and Order, sec. II(C) -(D), pgs. 9 - 12]. Aptheker v. Secretary-of State, 378 U.S. 500 (1964); United States v. Robel, 389 U.S. 258 (1967); Scales v. United States, 367 U.S. 203 (1961); United States v. Lemon, 723 F.2d 922 (D.C. Cir. 1983); Noto v. United States, 367 U.S. 290 (1961). The State can no more rely upon such a theory to support the search warrant than it can to support the petition. Even with the assistance of this unavailable theory, however, particularized probable cause does not exist.

B.

As to each of the items "enumerated" in the search warrant there is no probable cause. The State, as has been seen, does not even attempt to show particularized reason to believe that "any and all children under the age of 18 found" were the victims of abuse. (Paragraph 1 of the Search Warrant).

There is no showing that "rods or paddles" would be located in any particular residence. (Paragraph 2 of the Search Warrant).

While "medical supplies, indicative of the illegal practice of medicine" might reasonably be expected to be found in the residence of one individual, a Mr. Cantwell, or in the so-called clinic, there is absolutely no basis to believe they might be found elsewhere. (Paragraph 3 of the Search warrant).

There is no mention anywhere that any "photographs of discipline and/or illegal practice of medicine" were ever taken or existed. (Paragraph 4 of the Search Warrant).

Likewise, there is only the reference to one letter from a Mr. Spriggs to an identified individual which supports a belief in the existence of letters or writings involving the physical discipline of children, education of children and/or illegal medical practices. (Paragraph 5 of the Search Warrant).